In 1894 St. Louisan John Buckner was abducted from police custody in Manchester, Missouri by a mob who transported him three miles to the area of Valley Park, where they killed him by hanging from a bridge over the Meramec River. No one was punished for the lynching.

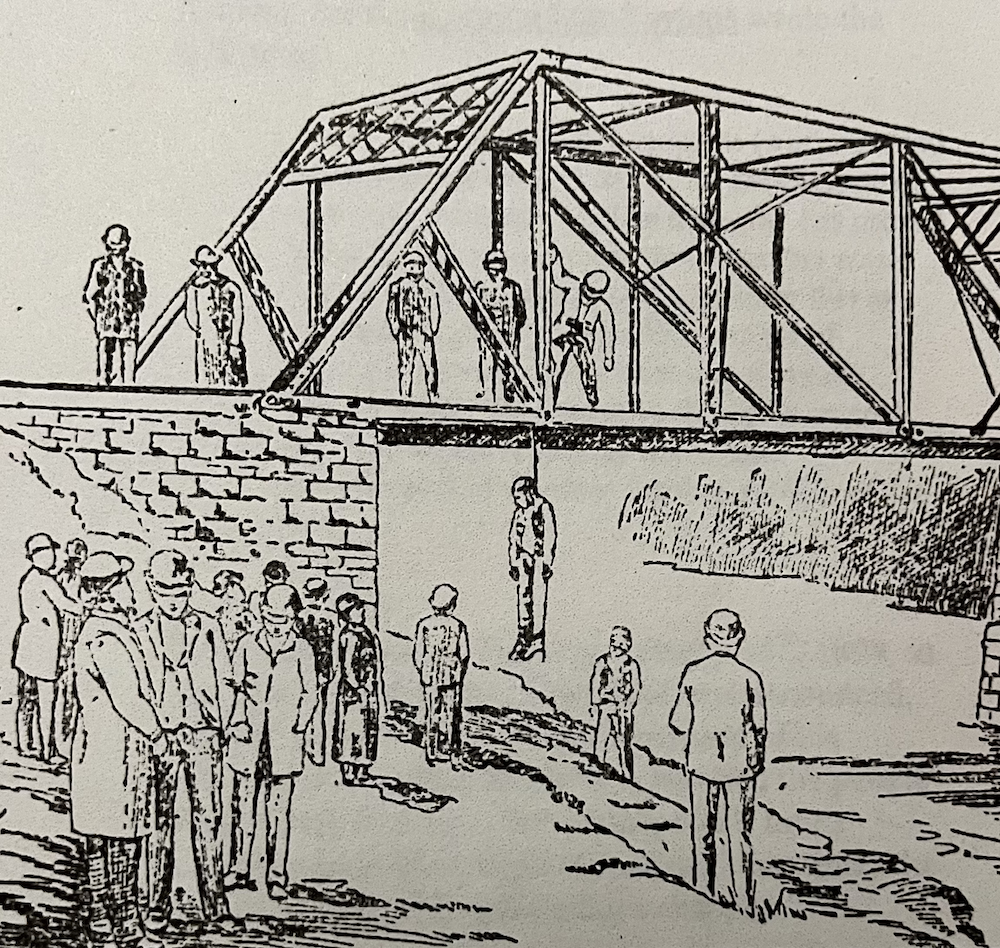

Image: Large crowds reportedly gathered the morning after the lynching to

view John Buckner’s corpse (Source: St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Jan. 18, 1894, p. 12).

Who Was John Buckner?

Soil Collection Ceremony

On January 17, 2022 the coalition held a Soil Collection Ceremony remembering the January 17, 1894 lynching of John Buckner in Valley Park. more

John Buckner was born in 1870, the grandson of one of the earliest free Black settlers in St. Louis County, from whom he took his name. The Buckner family was comprised of the eight children of John and Vinette Buckner, who had moved to St. Louis from Kentucky in the mid-nineteenth century: the youngest, Freeman, was named after the Emancipation Proclamation issued in 1863, the year of his birth. He followed siblings Joseph, James, Sarah, Lewis, Mary, John, and William. William was the father of John Buckner and three other children — Eliza, James, and Elisha. The Buckners lived in a hilly area just south of the Meramec River, along the Hawkins Road; three miles south of the town of Valley Park. The Buckner men were laborers and farmers, as were most other Black men in the area, and members of the Buckner family were land owners.

Denials of Justice

On January 16, 1894, John Buckner was accused of the attempted rape of a young white woman, and also of raping an older black woman who was a neighbor to his family home, in separate incidents. Five years earlier (1889), at age 17, Buckner was convicted of assault with attempt to rape an African American teacher, for which he was incarcerated for several years. Following the 1894 allegation the local Constable, Nicholas Schumacher, arrested John Buckner at his family’s home a few miles south of Valley Park, then immediately transported him on horse to the nearby city of Manchester, traveling past angry people near Valley Park who wanted to lynch Buckner, some of them shouting “String ‘em! String ‘em,” according to reports.

In Manchester, Justice Frank Hoffstetter ordered that Buckner be held in the County Jail in Clayton, but Schumacher felt he could not safely transport him that evening due to the late hour and cold temperature. An armed lynch mob had gathered and Schumacher decided to hide Buckner in Hoffstetter’s cellar until morning.

In the early morning hours of January 17, a mob reported to include 25 to 30 masked men, armed with shotguns and rifles, came to Hofstetter’s building, broke through the heavy oak doors, assaulted the guard protecting him, and abducted Buckner. The mob debated whether to shoot Buckner on the spot, hang him from a nearby telegraph pole, or take him back to Valley Park.

The leaders of the mob decided to take John Buckner to Valley Park. One of the women who accused Buckner of assaulting her was there and confronted him, identifying him as her assailant. The mob then tied a coil of rope around John Buckner’s neck, and threw him over the rail of the bridge, killing him.

The location where John Buckner was hanged, near the highway 141 bridge over the Meramec River in Valley Park, MO.

“The people want no inquiry”

After murdering John Buckner, the mob crept away, and was never publicly identified. According to a newspaper story the next day, “Vast crowds visited the scene all morning, and viewed the ghastly corpse hanging in the bright sunlight. No arrests have been made up to 2 p..m today, although it is possible that all the lynchers will soon be known.”

In fact, there was no serious attempt to uncover or reveal the identities of the lynch mob. Another news story that day (below) reported that county authorities determined there would be “no investigation” of the lynching, and that most white residents regarded the lynching as “a good work well done.” Justice Hofstetter, acting as Deputy Coroner, gathered a jury of Valley Park citizens to hold an inquest into Buckner’s death, which rendered the verdict: “We, the jury, find the deceased, John Buckner, came to his death by hanging at the hands of parties unknown to the jury.” None of the lynch mob were ever charged.

January 18, 1894 St. Louis Post-Dispatch article announcing there would be no investigation of the lynching of John Buckner.

The need for community remembrance

We commemorate this case to publicly acknowledge and condemn the denials of justice reflected in the planning, execution, and aftermath of the lynching: the denial of the presumption of innocence and other due process protections, the failure of law enforcement to protect the accused, the lynching itself, and the failure of white authorities and residents to hold the mob accountable. As in the case of the lynching of Francis McIntosh sixty years earlier, a jury was convened to consider indictments in the lynching of John Buckner, but no indictments were made, the mob went unpunished, and “lynch law” was endorsed. These local cases illustrate how racial terror lynchings brutalized our culture, normalizing disregard for African American human and civil rights.

We need to remember this injustice because we remain impacted by legacies of lynching. This history of routine denial of constitutional rights to equal protection helped shape persistent patterns including interpersonal and state violence, the crisis of mass incarceration and other punitive excess, and the enduring racial disparity of the death penalty - which EJI explains is, “a direct descendant of lynching.” As we continue to struggle for equal recognition and protection under law in our city, state, and nation, we remember the Buckner lynching and subsequent denial of justice to join in opposition to this past and still present injustice.

Illustration of the scene of the lynching the morning after (Source: St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Jan. 18, 1894, p. 12).

Read the EJI narrative in remembrance of John Buckner:

For details about the John Buckner Remembrance Events please visit our events page: